Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) are prevalent in tropical climates, disproportionately affecting the most impoverished communities. Their global incidence hinders the development of millions of people around the world.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are 20 neglected diseases in the world that affect more than 1 billion people. NTDs are neglected diseases because they mainly affect people living in rural, remote and impoverished areas of the tropics.

NTDs are transmitted by vectors that result from complex biological cycles through pathogens such as parasites, bacteria, fungi, toxins and viruses. Among other factors, their transmission is attributed to difficulties in accessing public health services and safe water, hygiene and sanitation in affected communities. They are also neglected because they are not a priority in global health programmes and funding.

The incidence of NTDs: a global health challenge

More than one billion people in 149 countries are affected by one of the 20 existing NTDs. This is why the World Health Organization (WHO) has published a roadmap pledging to reduce them by 90% by 2030.

Moreover, the objective the WHO has set for 2030 is that 70% of cases receiving treatment will have been previously diagnosed, and this implies a twofold focus. On the one hand, improving diagnostic tools by making them more accessible, usable and reliable. And, on the other hand, having reliable treatments that can be provided in contexts as challenging as those in which NTDs occur.

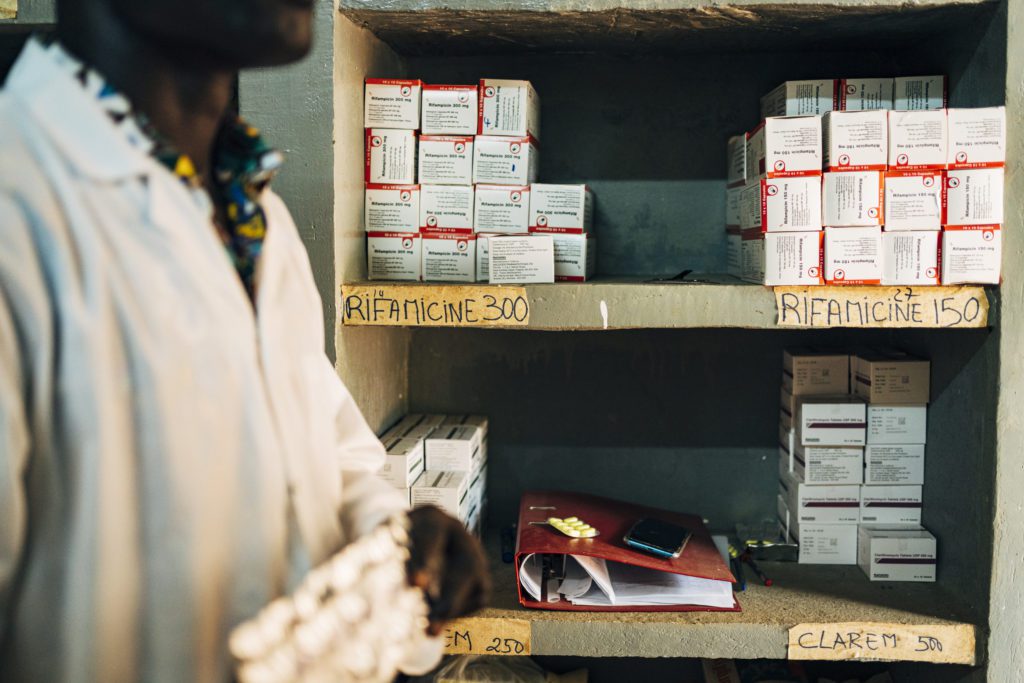

At the Anesvad Foundation, we work in four countries in sub-Saharan Africa—Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin—to control, eliminate and eradicate four skin NTDs: leprosy, Buruli ulcer, yaws and lymphatic filariasis.

Case detection, the key to controlling skin NTDs

The major challenge with neglected diseases lies in their detection, particularly because they affect people in the most rural, remote settings, where people often do not even know they are ill. These figures on diagnosed cases fall short of representing the total number of people affected in the world.

The skin NTDs we work with, such as yaws, Buruli ulcer and leprosy, do not report a large number of new cases, but there is a high level of under-reporting. That is why we are committed to active case detection, that is, going out in the field to look for the disease, not waiting for people who feel ill to go to health centres. We also promote awareness-raising initiatives in affected communities so that people go to their health centres when they identify symptoms and can be diagnosed and treated, interrupting transmission and stopping contagion.

How are skin NTDs diagnosed?

Skin NTDs can be diagnosed clinically through a visual examination. The accuracy of the clinical diagnosis depends on the level of expertise of the healthcare staff performing the test. Therefore, training is essential when it comes to the early detection of these diseases.

Although skin manifestations can partially provide a clinical diagnosis, confirmation can often only be made by detecting the presence of a pathogen (antigen) or evidence of an immune response to infection (antibodies).

There is a gap here in the way different skin NTDs are diagnosed. Efforts are being made to have some of them diagnosed close to where the patients are. However, only a rapid diagnostic test is currently available for lymphatic filariasis and yaws. Other rapid diagnostic tests for Buruli ulcer, leprosy and cutaneous leishmaniasis are being developed but are not yet available.

There are also research projects that are exploring multiple platforms for the simultaneous diagnosis of several skin NTDs. Much of the work relates to serosurveillance, which is the method most likely to be integrated for surveillance of multiple skin and other NTDs.

While these gaps are being addressed, several laboratory methods already exist to confirm the diagnosis of many skin NTDs. These conventional methods include microscopy, culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and dermatopathology. Although these methods are not always easy to apply in the field or available in some situations, they often remain the only way to confirm cases. Facilities and equipment, as well as capacity building to perform these tests, vary from country to country, so diagnostic time may also vary.

Therefore, to detect NTDs early and prevent the suffering of those afflicted, support for laboratory diagnosis must be strengthened. At the Anesvad Foundation, we are committed to research into new diagnostic methods that are faster, more effective and closer to patients, which will improve health care and prevent disabilities associated with skin NTDs.